NONA

Mark Markin

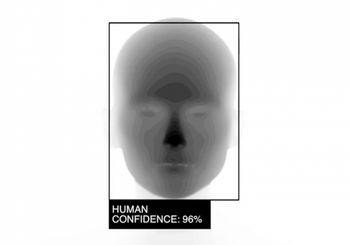

A computer’s facial recognition system has broadly the same components as your own facial recognition system. You see someone with your eyes, your mind processes the features of their face, and recalls their identity from your memory. Now imagine if you could have eyes in lots of places and could download and store memories from other people — then you will have something more like the automated version of facial recognition.

Its eyes are digital cameras, revolutionary machines that turn light into data. The “mind” of facial recognition systems is made up of a series of algorithms. They locate faces in an image, map facial features to correct for head rotation, and then take over 100 measurements that define that individual face. Those measurements are usually described as the distance between the eyes, the length of the nose, the width of the mouth. But whoever uses that software won’t be able to identify you until you’re in their database of known faces. That’s the “memory” of the system – and it’s separate from the training images.

Companies like Facebook and Google also keep databases of their users. It is governments that typically have access to the largest databases of names and faces, so facial recognition significantly expands the power of the state. They collected these images for other reasons and now they’re repurposing them for facial recognition without telling us or obtaining our consent, which is why several US cities have banned government use of facial recognition.

Then there is another source of labeled photos. Those are the ones we have been labelling ourselves by setting up profiles on social media networks. It is typically against the terms of use to program bots that can download faces and names from Instagram, Twitter, of Facebook, but it is doable. And what’s at stake is something that most of us take for granted: our ability to move through public spaces anonymously. Are we allowed to want to share and connect with other people online, and still be able to expect not to be recognised when we are offline in our regular lives?

Having any individuality requires experimenting in life and this procedure requires the protections of some obscurity. But also intimacy requires obscurity. If you want to be able to share different parts of your life with different people, we must be able to do it freely. We do not want to come into work and behave the same way we do with our friends. We do not want to treat our partners in the same way we do acquaintances. The concern, when you lose too much obscurity, is that these domains bleed into one another and create what’s called “context collapse”. It does not mean that one is more real or one is more authentic. Leading a rich life requires us to be able to express ourselves in these diverse ways.

The photos we took to share with friends, document history, or simply get a government ID, have been used to build and operate a technology that strips away the protections that obscurity has always provided us. It is not that much different from your typical bait-and-switch and it is one that could change the meaning of the human face forever.

Nevertheless, NONA was not made as mask to hide or critique against our society. Instead, it is a visualisation of the interaction between human’s facial biometric datas captured by machine vision, and is processed by nature’s algorithms.